Discussion on the Flying Rivers of the Amazon and their importance. All images credit: Women4Biodiversity

The Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) is an intergovernmental organisation constituted by the eight Amazonian countries of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela that signed the Amazon Cooperation Treaty (ACT), establishing the only socio-environmental bloc in Latin America. Its mandate is to identify the medium-term priorities of the Amazonian countries, in line with the region’s economic, political, environmental, and social realities.

This year, the Amazon Regional Meeting was held in Bogotá, Colombia. From 18 August to 22 August, civil society representatives, Indigenous peoples, local communities, academia, and other sectors were brought together. The V Amazon Summit of Heads of State took place immediately, from 22 August 22 to 23 August 2025. It was a high-level political space to consolidate common positions among the Member States. Both processes are framed as a continuation of the Belém Declaration (2023), which established 113 objectives for protecting the Amazon and reducing inequalities, and as preparation for the UN Climate Change Conference (COP30) in Belém (2025).

The Summit took place in a context marked by the intensification of extractive activities, the expansion of drug trafficking and criminal networks, all of which severely impact the integrity of the biome.

- Deforestation: Between 2015 and 2020, the Amazon lost around 23.7 million hectares of forest (an area almost the size of the United Kingdom). In 2022, deforestation in the Amazon reached approximately 1.98 million hectares, 21% more than in 2021, making it the worst year since 2004.

- Tipping point: The Amazon has lost approximately 17% of its original forests, and another 17% is degraded. This situation is approaching the critical threshold of 20–25%; if reached, it would trigger the collapse of local rainfall and the transformation of the Amazon into a savanna.

- Mercury contamination: Artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) is the main source of contamination, responsible for 71% of emissions. In the Peruvian Amazon alone, around 185 tons of mercury are released into rivers every year.

- Forest fires: Fire seasons are becoming increasingly severe. 2024 broke all records, with Brazil losing approximately 2.8 million hectares of tropical forest. Although more than 95% of Amazonian fires are caused by human activities (land clearing, etc.), the combination of deforestation and drought has made the forest far more flammable.

- Changes in climate patterns: In the past, major droughts occurred roughly every 20 years; now they are more frequent (six occurred between 2005–2024). The 2024 drought brought up to 70% less rainfall in some areas, triggering water crises in several communities. At the same time, extreme floods have also become more frequent. Rainfall patterns have shifted: the dry season has lengthened, while the wet season has shortened.

Carlos Lleras Restrepo National University Newspaper Library in Bogotá, Colombia, headquarters of the ACTO.

At the Amazon Regional Meeting, a wide range of proposals were presented by representatives of civil society, academia, Indigenous Peoples’ and Local Communities, among which the following stand out:

- Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities must fully and effectively participate in the entire decision-making process affecting their ancestral territories, not only at the final stage when policies or projects are already underway.

- Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) is a right that is systematically violated. The most recent case is the proposal for the Peru–Ecuador binational oil pipeline, promoted by the Peruvian presidency in July 2025 without any prior consultation process, thus violating national laws and international treaties. If implemented, this project would not only increase the risks of oil spills (Peru registers an average of 148 spills annually), but the pipeline would also cross the traditional territories of the Achuar, Wampís, and Chapra peoples.

- The Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty was highlighted as a global initiative to stop the expansion of new fossil fuel projects, phase out existing production, and ensure a just and equitable transition to renewable energy sources.

- Financing mechanisms that are direct, timely, and flexible, recognising the contributions of Indigenous peoples and local communities, with differentiated access opportunities for women and youth.

The central focus of the summit was the adoption of the Bogotá Declaration, a document containing 32 points and 20 resolutions. These included commitments on:

- The creation of institutional and financial mechanisms to strengthen ACTO and ensure the implementation of regional initiatives.

- Measures on climate risk, food security, and health, framed under the principle of “One Health.”

- The recognition of the rights, governance systems, and ancestral knowledge of Indigenous peoples, with the creation of the Amazonian Indigenous Peoples Mechanism (MAPI). A historic outcome, for the first time in its 45 years of existence, ACTO will have a permanent channel for dialogue with Indigenous peoples. MAPI can transform governance by recognising Indigenous autonomy, guaranteeing Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), and ensuring representation in decision-making.

- Commitments to strengthen deforestation monitoring, regional cooperation in law enforcement, and the fight against illicit economies that threaten the biome.

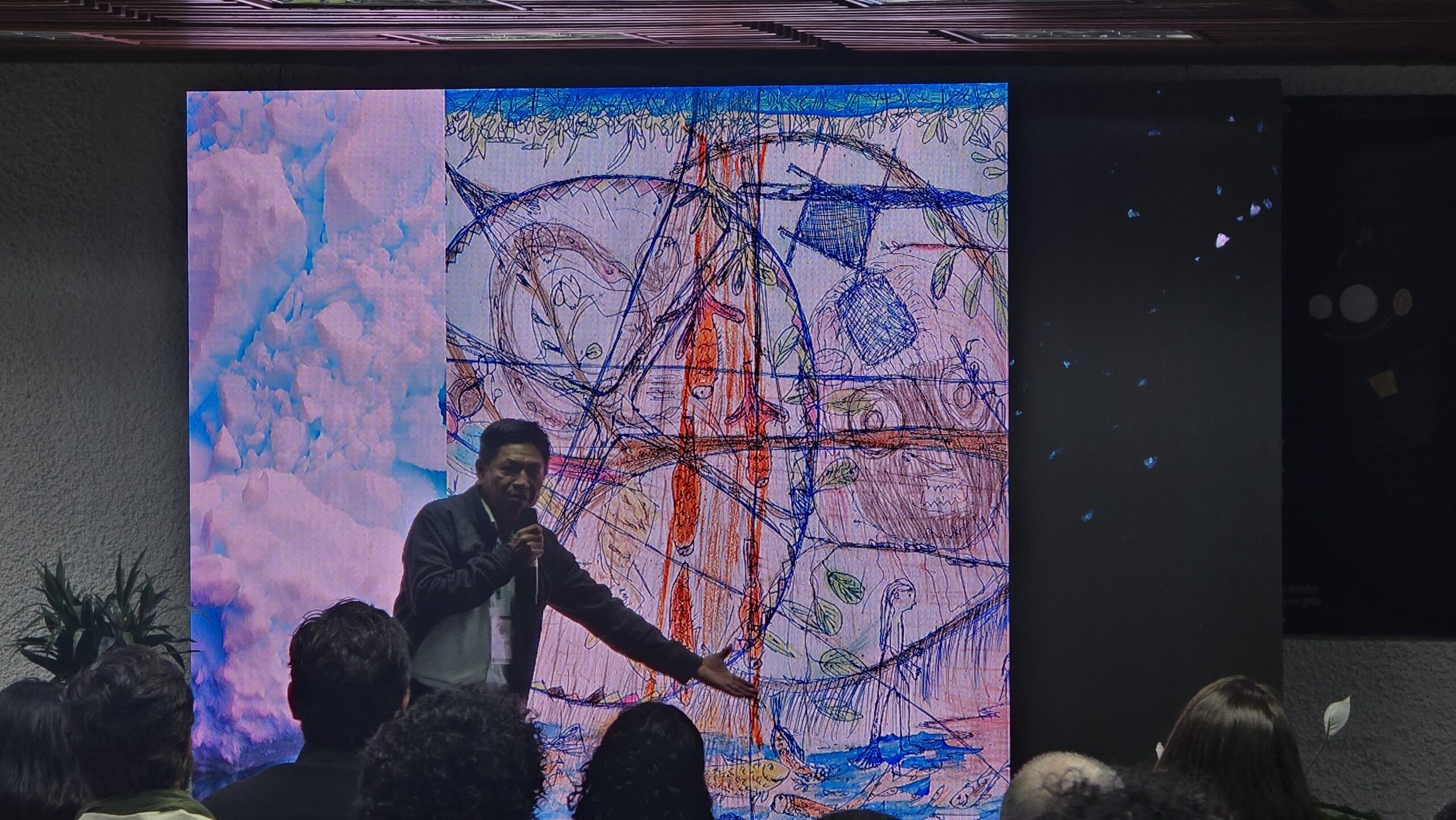

Discussion on the Flying Rivers of the Amazon with a graphic explanation of the connections between groundwater, evapotranspiration in the Amazon rainforest, and trees.

However, the declaration did not explicitly mention the progressive elimination of fossil fuels and did not include binding commitments to halt deforestation by 2030. This omission reflects the tensions between countries advocating for a rapid energy transition and those maintaining an interest in fossil fuel development. Moreover, a Civil Society Participation Mechanism was not consolidated, despite being backed by more than 450 organisations. This is particularly problematic given that contributions from civil society are essential for effective solutions.

Another point of debate was the launch of the Tropical Forests Forever Fund (TFFF), which was proposed by a senior World Bank official more than 15 years ago and promoted by Brazil at this Summit. Its objective is to mobilise 2.8 billion dollars annually through contributions from governments and private actors. The fund was received both as an innovation and as a way of privatising tropical forest financing in an insufficient manner, benefiting existing power dynamics and undermining Indigenous peoples and local communities. At the same time, questions remain regarding its governance, safeguards, and operationalisation.

Alejandra Duarte, Research & Policy Associate, Women4Biodiversity.

The Bogotá Summit consolidated a unified agenda of the Amazonian countries for COP30 in Belém. The Bogotá Declaration also includes commitments to align national climate plans (NDCs) with regional policies and to position the Amazon as a central theme in global climate negotiations. Nevertheless, concerns persist regarding the lack of explicit commitments to phase out fossil fuels, the limited operationalisation of MAPI, and the absence of a civil society mechanism. The V Amazon Summit in Bogotá represented an important step in strengthening regional cooperation and the institutional architecture of ACTO. As the Amazon approaches a dangerous ecological tipping point, the credibility of Amazonian leadership will depend on whether these commitments are transformed into concrete actions. COP30 in Belém will be the decisive stage, only with the full participation of Indigenous Peoples’ and civil society, robust and accessible financing, and a clear path toward a just transition and zero deforestation will it be possible to secure the future of the Amazon.